Thomas Brady

Convict Rebel

Thomas Brady was born in County Wicklow, Ireland in 1754.

He was recorded as a farmer in the Journal of surgeon John Washington Price kept on the voyage of the convict ship Minerva in 1800 [2] Joseph Holt in his memoirs refers to him as Chief Clerk employed at the Wicklow Gold mine and it seems that this may have been his main occupation given his employment later in New South Wales.

United Irishmen

It has been written that British rule in Ireland in the eighteenth century was one of the grossest and most malignant stories of oppression in history as England struggled to maintain her control, promoting the religious differences between Catholics and Dissenters from the north. In order for Ireland to obtain her freedom from the British it was necessary to form a union of the two religious groups. Theobald Wolfe Tone, a young Protestant barrister, set out to join the Catholics and Presbyterian dissenters in a union intended to shake off the shackles of English dominance and exploitation. England threw all her power into crushing the union of Catholics and Dissenters however by the end of 1796 membership of the United Irishmen was said to be half a million and consisted of men of all walks of life including priests.[1]Wicklow

Thomas Brady was affiliated with the United Irishmen. He was arrested in Wicklow possibly early in March 1798 and was tried in that month with many others including John Austin, Brien Byrne, Richard Byrne, Benjamin Carrol, Christopher Coleman, John Davis, Robert Doogan, Partrick Duffy, Thomas Ennis, Roger Gavin, John Hewitt, Robert Keane, John Kinkaid, John McDonald, Joseph McKinly, Charles McClean Ferdinand Maurant, Joseph Murray, Michael Mulhall, William Noble, Owen Nugent, John Reddington, William Russell and Robert Wilson.Banishment Act

Following his trial in March 1798, Thomas Brady was named in the Banishment Act and would become a voluntary exile [2].The Banishment Act (38 George III, c.78) pardoned named individuals concerned in a rebellion. Return to British dominions or passage to a country at war with Britain were prohibited [5]

There were approximately 100 Wicklow men transported after the rebellion of 1798. Another 500 from other counties would also join them in Australia [4]

Wicklow Gaol

Many of these men were probably held in the Wicklow gaol along with Thomas Brady to await transportation. Some of the rebels such as Billy Byrne were hanged in or near the Gaol [4]Martial Law

Martial Law was proclaimed on 30th March 1798 and under its shelter, British troops committed a wave of atrocities.General Joseph Holt

Joseph Holt who would come to be revered for his leadership and military prowess took to the Wicklow mountains in May 1798 after his house had been burned to the ground. Holt led a series of fierce raids and ambushes against loyalist military targets in Wicklow. [1]Vinegar Hill

The defeat of rebels at Vinegar Hill saw the remainder of the men heading to the Wicklow Mountains to link up with Holt and his men. Under Holt's command a force of British cavalry were defeated, although subsequent campaigns were disastrous and the uprising collapsed. The rebels continued their guerrilla campaign from the Wicklow Mountains, however Joseph Holt negotiated surrender for himself and many men were also captured. The war would continue under the leadership of the intrepid Michael Dwyer.On Board the Lively

Eventually transport was arranged for Thomas Brady and the other prisoners held in Wicklow. One hundred and thirty-seven convicts, 19 of whom were female were put on the vessel 'Lively' under Captain Dobson. They probably boarded the Lively in May [6] and remained on board for up to seven months waiting to be taken to Cork, there to be embarked on the Minerva transport. Some of the mess mates of Thomas Brady on the Lively included: John Lacy, of Dublin, metal founder; Joseph Davis, of Dublin, cutler; Farrell Cuffee of the King's County, schoolmaster; John Kincaid of Armagh; William Henry of Armagh; Charles Dean of Dublin, apothecary's apprentice; Richard Day (?Dry); Samuel Car, brother to a clergyman of Armagh; and Joseph Holt.In his memoirs, Joseph Holt described the appalling conditions and lack of food on the Lively:

Dobson had agreed with Government to take us to Cork for a stipulated sum, and to supply us with a pound of meat, and a pound of bread each day. In order to make this scanty allowance go farther, he appointed a person to distribute it with light weights, so as to give but seven instead of ten pounds. It was no use to remonstrate; any one who complained was instantly chained to the deck of the vessel. The hatchways were left open to prevent our being suffocated. In the centre of the vessel a large tub was placed for the accommodation of eighty persons, not one of whom was allowed to go on deck at night, and who were mostly fresh water sailors This disgusting and horrible tub was emptied but once in twenty four hours, and as the motion of the vessel kept it in a continued state of evaporation, the atmosphere we were compelled to breathe cannot easily be even imaged. It is not to be wondered at then, that those whose frames and constitutions were delicate, sunk under the misery of our situation. Frosty winds with rain and sleet prevailed'

A plank was their path by day and their bed at night and as the vessel rolled, the bilge water would flash under them. Two years Holt's senior, Thomas Brady was concerned for his leader's welfare. Holt in his memoirs records that Brady shared his pillow which was a lock of hay and he recorded a conversation with Brady. Mr. Brady said to me, 'This is a most wretched lodging for you. It is I replied, but I have seen much hardship; my God has ever been propitious to me, and I doubt not I shall have his support' [12]

On the 2nd January 1799 Dobson received orders to sail and on the 3rd Thomas Brady for the last time gazed on the Wicklow Mountains, where according to Holt they had been contented, prosperous, respected and beloved.

Cork

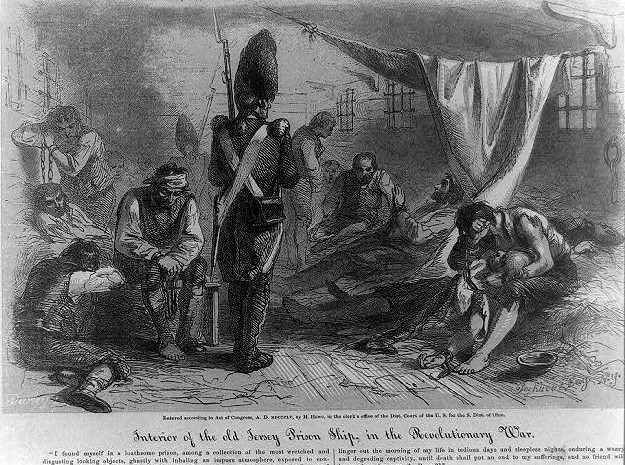

The Lively arrived in Cork on 29th January 1799. John Washington Price, surgeon of the Minerva had long been expecting the arrival of the Lively and he immediately boarded her to examine the convicts. He found them in a most wretched, cruel and pitiable condition, lying indiscriminately in the ships hold on damp wet and uneven planks without any covering, half naked and exposed to all inclemencies of the season whether snow, frost or rain. He had never seen a more unhealthy looking or miserable set of human beings in his life. There was little he could do for them however while they lay in the hold of the Lively, even as the weather worsened and men began to die.[2]Image: Interior of a prison ship:

Convict Ship Minerva

They were not taken on board the Minerva until the 13th February and over the next few months, prisoners from Cork joined them as well. Before being taken on board the Minerva they had their heads shaved. They were washed and received a new set of clothing and bedding consisting of 2 jackets, 2 pair of trousers, 2 shirts, 2 pair of shoes, 2 pair of stockings, a cap, hat, vest, mattress, pair of blankets, and cloth bags. Once on board the Minerva they were attended by John Washington Price who suggested fresh food be procured and who ensured the living quarters remained clean and airy. The prisoners slept five to each berth and the quarters were 8 feet high between decks with a scuttle one foot square to each berth on each side of the ship.[2]Departure

The Minerva departed Cork on Saturday 24th August. As well as the convicts and a detachment of the N.S.W. Corps under Lieut. William Cox and passengers such as artist John William Lewin, the Minerva carried stores - including 25 pipes spirits, 6 tons sugar, 20 cases glass, 4 casks ironware, 5 casks molasses, 60 pieces Irish linen, 4 boxes coffee, 150 bales Rio tobacco, 2trunks shoes, 20 casks provisions, 15 furkins butter, 1 box hair powder, 4 pipes port wine.The Voyage

Their voyage to Australia was not without incident. In an account of the Minerva's contact with Spanish frigates, in Joseph Holt's memoirs Holt mentions Thomas Brady as one of his 'good and resolute men' -On the 16th November we saw a sail to windward, which chased us for two days: she showed Spanish colours, and we thought her a frigate. But the Minerva was good sailer and beat her by chalks. We ran at least nine knots an hour, and effected our escape. Two days after we discovered two sail to leeward. The captain said one was a Spanish galleon, the other a prison ship. He gave orders to clear the ship for action. We had eight guns and two swivels on the poop.

Mr. Harrison (Henry Harrison, chief mate) asked if I would fight. I answered Yes and requested to be allowed to choose from among the prisoners the requisite number of men to work the gun and he gave orders that I should have any I chose, on which I called for John Kincaid, Richard Byrne, Joseph Davis, Thomas Brady, Martin Short, and Pat Whelan, six good and resolute men on whom I could depend.

I then got my cartridges, hands spikes, ramrods, tub flame, and powder monkey. I was soon charged and ready. I passed the word to Kincaid and Byrne to mind my motions and not to fire till I gave the signal. Captain Cox was on the poop with 24 marines.' However, after a broadside which did them no harm, the Minerva managed to out run the Frigate' [12]

Ever the soldier, Joseph Holt went on to explain the reason for his involvement Mr. Harrison, till this day I considered you a sagacious man. What have I done, sir said he, To change your opinion of me?

I will tell you I answered, you know that although I am no convict, I am under restraint, and if I was taken by any power I would demand the rights and privileges of a citizen of that power. It was my interest and the intention of the men you gave me from among the prisoners, that we should be captured. All who are enemies to England are our friends; we are in a state of bondmen to England; with the Spaniards we should be free. Had England given us freedom, we should have been grateful and delighted to fight for her; but she placed us in chains how could you think we would fight to keep ourselves in irons? No, sir, I tell you had we come to action, I would have turned the gun against the poop, and tried all I could to obtain liberty for myself and the other prisoners. All nations of the world are our friends, save England only'.[12]

Washington Price records the above incident as having taken place in September. He makes no mention of assistance from Joseph Holt or his resolute men but does question the wisdom of allowing the frigates to come so close and regret at having his cabin pulled down and furniture removed to make way for a gun. Washington Price makes mention of Spanish frigates in his entry for November 'The convicts begin now to get great spirits from an idea that has been formed by one of their chiefs that we are to be met when in the latitude of the Cape by two Spanish or French vessels, and brought into the Isle of France, but I am apt to think that they will be disappointed, and do suppose that the proprietor of this falsehood, (O'Connor the Bantry doctor) could have no other motive in it , but a view of alienating the minds of the people who were well disposed in the ship, and thus by threat and holding forth this language, induce them, to make attempts they would otherwise never think of ; but we shall take care not to give him or any of the rest of them an opportunity. [2]

Rio de Janeiro

The Minerva reached Rio de Janeiro on Sunday 20th October and departed on 8th NovemberPort Jackson

She arrived at Port Jackson on Sunday 12th January. Washington Price records the day as being exceedingly warm, the thermometer reaching 81F (29C) with a moderate South East breeze and clear skies.Convict Muster

After muster following the day of arrival the convicts were placed under an overseer and marched away to their different employments. Joseph Holt records that those transported for rebellion were left at large to act as they thought proper. 'Thomas Prosser, Thomas Brady, Edward O'Hara (and himself), all United Irishmen in alike circumstances agreed to walk out together. All respectable men their only crime was wrong notions in politics'[12]. Washington Price has a different version 'His Excellency Governor Hunter told me he had received many petitions and applications from the prisoners on board to be left here. He asked my opinion of many of them which I gave him candidly, in consequence of which John Austin, Ferdinand Maurant, Thomas Prosser, Dudley Hartigan, William Henry Alcock, Henry Fulton, Maurice Fitzgerald and Thomas Gosgrave were ordered ashore and the rest got absolute denials'.Irish Conspiracy

Nine months later in September 1800 an Irish conspiracy was uncovered. The plan was to overturn the government by putting Governor King to Death and confining Governor Hunter. The rebels were to meet at and take Parramatta and then before day light take the Barracks at Sydney. And afterwards to live on the Farms of the Settlers until they heard from France where they had intended to dispatch a ship. The rebels were well armed with pikes and were to be joined by soldiers who it was planned would take the guns to South Head and other places of security. When the plan was revealed, Governor Hunter ordered an Enquiry and many of Thomas Brady's acquaintances were questioned. Punishment for the perpetrators was harsh. The following correspondence written in October was received in England the next year:A very unpleasant circumstance had like to have occurred here lately. The Irish rebels who were lately transported into this country, had imported with them their dangerous principles, rather increased than subdued by their removal from their native country. They began by circulating their doctrines among the convicts and a conspiracy had scarcely been formed before it was happily discovered. They could never have attained their object; but from their desperation, infatuation, and sanguinary habits, much bloodshed would probably have ensued. They had conducted their scheme with great art and secrecy, to which they were generally sworn, and offensive weapons were made even from the tools of agriculture, for carrying their purpose into execution. In no part of the British dominions, upon any occasion, could the troops and principal inhabitants shew more zeal and alacrity in coming forward in support of the Government, and even some of the worst of the English convicts expressed their abhorrence of such a diabolical plan. Governor King has added to the military force, by forming a company at each settlement of the principal inhabitants; and which he has named The Loyal Parramatta and Sydney Association [8]

Thomas Brady was either not involved in this conspiracy or evaded detection.

Rebellion at Castle Hill

He was employed in the Commissary's office for four years following arrival in Sydney and it is almost certain he maintained his allegiance to his fellow countrymen in exile. Although he was not implicated in the 1800 rebellion he was not so fortunate in 1804. In the aftermath of the Rebellion at Castle Hill, an inflammatory letter written by him was found amongst the papers of a 'strongly suspected character. The letter contained terms and expressions of a virulent and seditious tendency and Brady was interrogated and brought before Governor King where his manner was generally impertinent and his whole conduct grossly insolent and disrespectful' He was ordered into the custody of the gaoler and to receive a corporal punishment.[7]Thomas Brady at Newcastle

After this punishment he was sent to Newcastle penal settlement.Select here to find other convicts sent to Coal River (Newcastle) in 1804. When he arrived at Newcastle or Coal River as it was often referred to in 1804, the settlement was under the Command of Lieutenant Charles Menzies. Many of Brady's contemporaries were put to work in the Coal Mines in Newcastle and it is possible that Brady was also required to do this work, however his usefulness as a clerk was recognized and he was probably employed in that capacity by the time Charles Throsby took over as Commandant twelve months later.

Under Lieutenant Menzies, conditions at Newcastle were necessarily strict and the work was arduous. There were many escape attempts and a foiled uprising by some of the convicts but no mention of any involvement by Thomas Brady. In fact Brady was to continue in Newcastle probably in the capacity of clerk or similar work throughout the tenure of several Commandants. It is possible he knew the running of the settlement better than anyone else during these early years. The first mention of him at Newcastle comes in the form of a rebuke by the benevolent Charles Throsby, and it is a mark of his regard for Brady that he dealt with the situation as he did. In another time under a different Commandant, Brady's punishment may have been much more severe. Charles Throsby had left instructions with the storekeeper Mr. Sutton that Thomas Brady was to assist in packing the salt ready to be taken to Sydney. Soon after, Throsby accompanied by Lieutenant Symons, went to examine the proceedings, and Throsby was embarrassed and annoyed by Thomas Brady's insolent behaviour towards him.[9]

He left instructions that Brady was not to be employed at the stores again but there is no mention of corporal punishment, isolation or any other punishment in fact which could have been expected in this time and place.

Governor Macquarie

Thomas Brady remained incarcerated at Newcastle throughout the entire upheaval with William Bligh and the New South Wales Corp in 1808-09, but he would not have been unaware of the events in Sydney. When Governor Macquarie arrived in the colony 1810 he issued a Proclamation stating that appointments, grants, leases, trials, and investigations under the rebel government were to be null and void. The direction was given that all men imprisoned while the rebel government was in place should be released.Imagine Thomas Brady's surprise when Commandant William Lawson gave the order that Brady too should be released, having 'served over five years at Newcastle and having in that time been a most useful man'.

Unfortunately Brady's freedom was short-lived for later in January several prisoners were returned to Newcastle and Lawson received advice that it was not His Excellency's wish nor the spirit of the recent Proclamation that every person who had incurred sentence of transportation under the late assumption of Government should indiscriminately be set free' only those who had been sentenced due to unjust causes. In future Lawson was to liberate only those persons whom the governor directed to liberate. Boat builder Thomas Crump and clerk Thomas Brady were found to have been liberated illegally and they were returned to Newcastle as was Irish lawyer Lawrence Davoran.[10]

Thomas Brady at Newcastle 1810 - 1812

In this tiny settlement of just 100 people, Brady remained for the next two years. He was in Newcastle when Lieutenant Purcell took over as Commandant in 1810 and when a new wharf was commenced to replace the one begun by Menzies six years before. He was there when Governor Macquarie Inspected the Township on 3rd January 1811 and a few months later when James Hardy Vaux arrived, under sentence to work in the coal mines. Thomas Brady was almost certainly close by when Lieutenant Purcell was engaged in a very public dispute with the new surgeon William Evans. He would have seen hundreds of convicts come and go during his long years at Coal River.Thomas Brady managed to procure a house for himself. Although the location of this is not revealed, it was substantial enough to be purchased for the use of the government in 1812 and Brady received 11 pounds remuneration. His circumstances were better than many in the settlement, however he was almost certainly glad to finally receive word that he had been granted a pardon. He departed the little settlement in January 1812.

Commissariat Department Sydney

It seems for the next few years he was employed as a clerk in the Commissariat Department in Sydney. While under the conditions of his Banishment he had not been permitted to return to Ireland, it is possible that he travelled elsewhere. He received an absolute pardon in 1812[2], and there is mention of a Thomas Brady departing the colony in the years 1813 and again in 1817 with a daughter; it is possible that the absolute pardon gave him the freedom to travel where he wished.Death

Thomas Brady died in Sydney on the 9th July 1819.[11]References

[1] Cargeeg, G., The Rebel of Glenmalure.,Hesperian Press Carlisle, W.A., 1988.[2] Fulton, P.J.(ed)., The Minerva Journal of John Washington Price, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 2000

[3] Chambers Edinburgh Journal

[4] Wicklow Historical Gaol site gaol

[5] Ireland - Chronology

[6]p7 Price states they had been living on a salt diet for seven months or more

[7] Sydney Gazette 25 March 1804

[8] Caledonian Mercury 18 June 1801

[9] Historical Records of New South Wales, Vol. VI, King and Bligh 1806, 1807, 1808. Edited by F. M. Bladen, Lansdowne Slattery and Company, Mona Vale, N.S.W.,1979. pp 836 - 841.

[10] Colonial Secretary's Letters 6002 4/3490Bp61

[11] Sydney Gazette 10 July 1819

[12] Croker, T. Crofton (ed)., Memoirs of Joseph Holt, 1838

↑