Expedition of Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell

1831

Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell was born in June 1792 at Grangemouth, Scotland, the son of John Mitchell and his wife Janet, nee Wilson. He arrived with his wife and family on the Prince Regent on 27 September 1827.

Surveyor-General

In 1828, on the death of John Oxley, Mitchell became surveyor-general; and in 1829 became responsible for the survey of roads and bridges. In 1830 he assumed responsibility for the Survey Department and by the end of 1830 Mitchell had made considerable changes in the roads from Sydney to Parramatta and to Liverpool; he had plotted a new road southwards through Berrima as far as Goulburn and had discovered and constructed a new western descent from the Blue Mountains towards Bathurst.Exploration

Following Governor Darling's departure from the colony, Mitchell was requested by acting Governor Patrick Lindesay to explore the area between the Castlereagh and Gwydir Rivers to test reports of captured bushranger George Clarke of the existence of a large river known as the Kindur flowing to the north-west.Extract from Diary 1831

Following are extracts from Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell's journal pertaining to his journey from Parramatta, through the Hunter and to the Liverpool Ranges..........After several weeks of anxious preparation, I had the satisfaction to find that every contingency was, as far as possible, provided for in my department...my last cares were to leave, in the hands of an engraver a map of the colony, that the past labours of the department might be permanently secured to the public, whatever might be our fate in the interior.

Little time remained for me to look at the sextants, theodolite and other instruments necessary for the exploratory journey; I collected in haste a few articles of personal equipment, and having as well as I could, under the circumstances, set my house in order, I bade adieu to my family, and left Sydney at noon on Thursday, the 24th day of November 1831, being accompanied for some miles by my friend Colonel Snodgrass.

30 November

- At length I had the satisfaction to see my party move forward in exploring order; it consisted of the following persons, viz.: -Carpenters - Alexander Burnett (per Lord Melville 1830) and Robert Whiting (possibly Ephraim Whiting per Sarah 1829);

Sailors - William Woods (Royal Charlotte 1825), John Palmer (Asia 1822), Thomas Jones, William Worthington (per Mellish 1829),

Medical Assistant - James Souter. (per Exmouth 1831)

Bullock Drivers - William Muirhead (Cawdry), Daniel Delaney (Asia 1822), James Forehan,

Groom - Joseph Jones (Albion 1827)

Blacksmith - Stephen Bombelli, (per Vittoria 1829)

Surveyor's Man - Timothy Cussack. (per Marquis of Huntley 1828)

Anthony Brown, Servant to me. (arrived per Edward in 1831)

Henry Dawkins, Servant to Mr. White.

These were the best men I could find. All were ready to face fire or water, in hopes of regaining by desperate exploits, a portion, at least, of that liberty which had been forfeited to the laws of their country. This was always a favourite service with the best disposed of the convict prisoners, for in the event of their meriting, by their good conduct, a favourable report on my return, the government was likely to grant them some indulgence.

I chose these men either from the characters they bore, or according to their trade or particular qualifications: Burnett was the son of a respectable house-carpenter on the banks of the Tweed, where he had been too fond of shooting game, his only cause of ' trouble.' Whiting, a Londoner, had been a soldier in the Guards. Woods had been found useful in the department as a surveyor's man; in which capacity he first came under my notice, after he had been long employed as a boatman in the survey of the coast, and having become, in consequence, ill from scurvy, he made application to me to be employed onshore. The justness of his request, and the services he had performed, prepossessed me in his favour, and I never afterwards had occasion to change my good opinion of him. John Palmer was a sailmaker as well as a sailor, and both he and Jones had been on board a man-of-war, and were very handy fellows. Worthington was a strong youth, recently arrived from Nottingham. He was nicknamed by his comrades ' Five o'clock,' from his having, on the outset of the journey, disturbed them by insisting that the hour was five o'clock soon after midnight, from his eagerness to be ready in time in the morning. I never saw Souter's diploma, but his experience and skill in surgery were sufficient to satisfy us, and to acquire for him from the men the appellation of ' Doctor.' Robert Muirhead had been a soldier in India, and banished, for some mutiny, to New South Wales; where his steady conduct had obtained for him an excellent character. Delaney and Foreham were experienced men in driving cattle. Joseph Jones, originally a London groom, I had always found intelligent and trust-worthy. Bombelli could shoe horses, and was afterwards transferred to my service by Mr. Sempill in lieu of a very turbulent character, whom I left behind, and who declared it to be his firm determination to be hanged. Cussack had been a bog surveyor in Ireland; he was an honest creature, but had got somehow implicated in a charge of administering unlawful oaths.

Of the above men, six men would also accompany Sir Thomas Mitchell's expedition in 1836 - Alexander Burnett, William Woods, John Palmer, Robert Muirhead, Joseph Jones, and Anthony Brown. After leaving Parramatta Mitchell and his party crossed the Hawkesbury river at Wiseman's Ferry and proceeded along the Great North Road .......

The country traversed by this new road is equally barren, and more mountainous than the district between Parramatta and the Hawkesbury. Amid those rocky heights and depths, across which I had recently toiled on foot, marking out with no ordinary labour, the intended line, I had now the satisfaction to trot over a new and level road, winding like a thread through the dreary labyrinth before me, and in which various parts had already acquired a local appellation not wholly unsuited to their character, such as ' Hungry Flat,' ' Devil's Backbone,' 'No-grass Valley,' and 'Dennis's Dog-kennel.' In fact, the whole face of the country is composed of sandstone rock, and but partially covered with vegetation.

Mitchell was accompanied along this part of the road by Percy Simpson. They stopped for a time beside a spring and Simpson produced a grilled fowl and feed for their horses. On their departure, Mitchell congratulated Simpson for his clever arrangements for opening the mountain road, a work which he had accomplished with small means, in nine months.

The horizon is only broken by one or two summits, which are different both in outline and quality from the surrounding country. The most remarkable is Warrawolong (Highest point in the Watagan Mountains) (- whose top I first observed from the hill of Jellore in the south, at the distance of 108 miles. This being a most important station for the general survey, which I made previously to opening the northern road, it was desirable to clear the summit, at least partly, of trees, a work which was accomplished after considerable labour - the trees having been very large. On removing the lofty forest, I found the view from that summit extended over a wild waste of rocky precipitous ravines, which debarred all access or passage in any direction, until I could patiently trace out the ridges between them, and for this purpose I ascended that hill on ten successive days, the whole of which time I devoted to the examination of the various outlines and their connections, by means of the theodolite.

Looking northward, an intermediate and lower range concealed from view the valley of the Hunter, but the summits of the Liverpool range appeared beyond it. On turning to the eastward, my view extended to the unpeopled shores and lonely waters of the vast Pacific. Not a trace of man, or of his existence, was visible on any side, except a distant solitary column of smoke, that arose from a thicket between the hill on which I stood and the coast, and marked the asylum of a remnant of the aborigines.

The remnant of the aboriginal tribe referred to by Mitchell was that of the Brisbane Water Tribe.....

These unfortunate creatures could no longer enjoy their solitary freedom; for the dominion of the white man surrounded them. His sheep and cattle filled the green pastures where the kangaroo (the principal food of the natives) was accustomed to range, until the stranger came from distant lands and claimed the soil. Thus these first inhabitants, hemmed in by the power of the white population, and deprived of the liberty which they formerly enjoyed of wandering at will through their native wilds, were compelled to seek a precarious shelter amidst the close thickets and rocky fastnesses which afforded them a temporary home, but scarcely a subsistence, for their chief support, the kangaroo, was either destroyed or banished. I knew this unhappy tribe, and had frequently met them in their haunts. In the prosecution of my surveys I was enabled to explore the wildest recesses of these deep mountainous ravines, guided occasionally by one or two of their number. I felt no hesitation in venturing amongst them, for, to me, they appeared a harmless unoffending race. On many a dark night, and even during rainy weather, I have proceeded on horseback amongst these steep and rocky ranges, my path being guided by two young boys belonging to the tribe, who ran cheerfully before my horse, alternately tearing off the stringy bark which served for torches, and setting fire to the grass trees (xanthorrhoea) to light my way.

26th November

- It was quite dark on the evening of the 26th November, before I reached the inn near the head of the little valley of the Wollombi, a tributary to the river Hunter. Here, at length, we again find some soil fit for cultivation, and the whole of it has been taken up in farms. But the pasturage afforded by the numerous vallies on this side of the mountains, here called 'cattle runs,' is more profitable to the owners of the farms, than the farms they actually possess, of which the produce by cultivation is only available to them at present, as the means of supporting grazing establishments. I should here observe, that in a climate so dry as that of Australia, the selection of farm land depends solely on the direction of streams, for it is only in the beds of water-courses, that any ponds can be found during dry seasons. The formation of reservoirs has not yet been resorted to, although the accidental largeness of ponds left in such channels has frequently determined settlers in their choice of a homestead, when by a little labour, a pond equally good might have been made in other parts, which few would select from the want of water. In the rocky gullies, that I had passed in these mountains, there was, probably, a sufficiency, but there was no land fit for the purposes of farming. In other situations, on the contrary, there might be found abundance of good soil, considered unavailable for any purpose except grazing, because it had no 'frontage' (as it is termed), on a river or chain of ponds. Selections have been frequently made of farms, which have thus excluded extensive tracts behind them from the water, and these remaining consequently unoccupied, have continued accessible only to the sheep or cattle of the possessor of the water frontage. In these vallies of the Upper Wollombi, we find little breadth of alluvial soil, but a never-failing supply of water has already attracted settlers to its banks - and those small farmers who live on a field or two of maize and potatoes - and who are the only beginning of an agricultural population, yet apparent, in New South Wales - shew a disposition to nestle in any available corner there. But on the lower portion of the Wollombi, where the valley widens, and water becomes less abundant, the soil being sandy, I found it impossible to locate some veterans on small farms, which I had marked out for them, because it was known that in dry seasons, although each farm had frontage on the Wollombi Brook, very few ponds remained in that part of its channel.November 27

. - Early this morning, I had a visit from Mr. (Heneage) Finch, who was very anxious that I should attach him to the exploring party. As I foresaw, that some delay might occur in procuring provisions, without his assistance, in this district, I accepted his services, and gave him his instructions, conditionally. I met Mr. White (George Boyle White) at the junction of the Ellalong, and we proceeded together, down the valley of the Wollombi. The sandstone terminates in cliffs on the right bank of this stream near the projected village of Broke, (named by me in honour of that meritorious officer, Sir Charles Broke Vere, Bart.) but the left bank is overlooked by other rocky extremities falling from the ranges on the west, until it reaches the main stream. The most conspicuous of these headlands, as they appear from that of 'Mattawee' behind the village of Broke, is called 'Wambo.' This consists of a dark mottled trap with crystals of felspar. But the most remarkable feature in this extensive valley, is the termination thereupon of the sandstone formation which renders barren so large a proportion of the surface of New South Wales. This, in many parts, resembles what was formerly called the iron-sand of England, where it occurs both as a fresh and salt water formation. The mountains northward of this valley of the Hunter consist chiefly of trap-rock, the lower country being open, and lightly wooded. The river, although occasionally stagnant, contains a permanent supply of water, and consequently the whole of the land on its banks, is favourable for the location of settlers, and accordingly has been all taken up. The country, and especially the hills beyond the left bank, affords excellent pasturage for sheep, as many large and thriving establishments testify. At one of this description, belonging to Mr. Blaxland, and which is situated on the bank of the Lower Wollombi, Mr. White and I arrived towards evening, and passed the night.November 28.

- We left the hospitable station of Mr. Blaxland at an early hour, and proceeded on our way to join the party. We found the country across which we rode, very much parched from the want of rain. The grass was every where yellow, or burnt up, and in many parts on fire, so that the smoke which arose from it obscured the sun, and added sensibly to the heat of the atmosphere. We lost ourselves, and, consequently, a good portion of the day, from having rode too carelessly through the forest country, while engaged in conversation respecting the intended journey. We, nevertheless, reached the place of rendezvous on Foy Brook long before night, and I encamped on a spot, where the whole party was to join me in the morning. Mr. White left me here for the purpose of making some arrangements at home, and respecting the supplies which I had calculated on obtaining in this part of the country.During the day's route, we traversed the valley of the river Hunter, an extensive tract of country, different from that mountainous region from which I had descended, inasmuch as it consists of low undulating land, thinly wooded, and bearing, in most parts, a good crop of grass. Portions of the surface near Mr. Blaxland's establishment, bore that peculiar, undulating character which appears in the southern districts, where it closely resembles furrows, and is termed ' ploughed ground.' This appearance usually indicates a good soil, which is either of a red or very dark colour, and in which small portions of trap-rock, but more frequently concretions of indurated marl, are found. Coal appears in the bed and banks of the Wollombi, near Mr. Blaxland's station, and at no great distance from his farm is a salt spring, also in the bed of this brook. The waters in the lesser tributaries, on the north bank of the river Hunter, become brackish when the current ceases. In that part of the bed of this river, which is nearest to the Wollombi (or to 'Wambo' rather), I found an augitic rock, consisting of a mixture of felspar and augite. Silicified fossil wood of a coniferous tree, is found abundantly in the plains, and in rounded pebbles in the banks and bed of the river, also chalcedony and compact brown haematite. A hill of some height on the right bank, situate twenty-six miles from the sea shore, is composed chiefly of a volcanic grit of greenish grey colour, consisting principally of felspar, and being in some parts slightly, in other parts highly calcareous when the rock assumes a compact aspect. This deposit contains numerous fossil shells, consisting chiefly of four distinct species of a new genus, nearest to hippopodium; also a new species of trochus; atrypa glabra, and spirifer, a shell occurring also in older limestones of England.

November 29

- The whole equipment came up at half past nine, whereupon I distributed such articles as were necessary to complete the organization of the party and the day was passed in making various arrangements for the better regulation of our proceedings both on encamping and in travelling. I obtained from Assistant Surveyor Robert Dixon, then employed in this neighbourhood, some account of Liverpool Plains - this officer having surveyed the ranges which separate these interior regions from the appropriated lands of the colony. The heat of this day was exceedingly oppressive, the thermometer having been as high as 100 in the shade but after a thunder shower it fell to 88.Thus it had been my study, in organizing this party, to combine proved men of both services with some neat-handed mechanics, as engineers, and it now formed a respectable body of men, for the purpose for which it was required. Our material consisted of eight muskets, six pistols; and our small stock of ammunition, including a box containing sky-rockets, was carried on one of the covered carts.

Of these tilted carts we had two, so constructed that they could be drawn either by one or two horses. They were also so light, that they could be moved across difficult passes by the men alone. Three stronger carts or drays were loaded with our stock of provisions, consisting of flour, pork (which had been boned in order to diminish the bulk as much as possible), tea, tobacco, sugar and soap. We had, besides, a sufficient number of pack saddles for the draught animals, that, in case of necessity, we might be able to carry forward the loads by such means. Several pack-horses were also attached to the party. I had been induced to prefer wheel carriages for an exploratory journey - 1st, From the level nature of the interior country; 2ndly, From the greater facility and certainty they afforded of starting early, and as the necessity for laying all our stores in separate loads on animals' backs could thus be avoided. The latter method being further exposed to interruptions on the way - by the derangement of loads - or galling the animals' backs - one inexperienced man being thus likely to impede the progress of the whole party.

For the navigation or passage of rivers, two portable boats of canvass, had been prepared by Mr. Eager, of the King's dockyard at Sydney. We carried the canvass only, with models of the ribs - and tools, having carpenters who could complete them, as occasions required.

Our hour for encamping, when circumstances permitted, was to be two P. M., as affording time for the cattle to feed and rest, but this depended on our finding water and grass. Day-break was to be the signal for preparing for the journey, and no time was allowed for breakfast, until after the party had encamped for the day.

As we proceeded along the road leading to the pass in the Liverpool range, Mr. White overtook us, having obtained an additional supply of flour, tobacco, tea and sugar, with which Mr. Finch was to follow the party as soon as he could procure the carts and bullocks necessary for the carriage of these stores.

After travelling six hours, we encamped beside a small water-course near Muscle Brook, the thermometer at four p. M. being as high as 95 degrees. In the evening, the burning grass became rather alarming, especially as we had a small stock of ammunition in one of the carts. I had established our camp to the windward of the burning grass, but I soon discovered that the progress of the fire was against the wind, especially where the grass was highest. This may appear strange, but it is easily accounted for. The extremities of the stalks bending from the wind, are the first to catch the flame, but as they become successively ignited, the fire runs directly to the windward, which is toward the lower end of the spikes of grass, and catching the extremities of other stalks still further in the direction of the wind, it travels in a similar manner along them. We managed to extinguish the burning grass before it reached our encampment, but to prevent the invasion of such a dangerous enemy we took the precaution, on other occasions, of burning a sufficient space around our tents in situations where we were exposed to like inconvenience and danger.

December 1,

6 am - The thermometer at 82 degrees. As the party proceeded, the sky became overcast, and the absence of the sun made the day much more agreeable. Towards noon we had rain and thunder, and this weather continued until we reached the banks of the Hunter. We forded the river where the stream was considerable at the time, and then encamped on the left bank. The draught animals appeared less fatigued by this journey, than they had been by that of the former day, owing probably to the refreshing moisture and cooler air. After the tents had been pitched, a fine invigorating breeze arose, and the weather cleared up. Segenhoe, the extensive estate of Potter Macqueen, Esq. was not far distant, and Mr. H.C. Sempill the agent, called at my tent, and afforded me some aid in completing my arrangements.I was very anxious to obtain the assistance of an aboriginal guide, but the natives had almost all disappeared from the valley of the Hunter; and those who still linger near their ancient haunts, are sometimes met with, about such large establishments as Segenhoe, where, it may be presumed, they meet with kind treatment. Their reckless gaiety of manner; intelligence respecting the country, expressed in a laughable inversion of slang words; their dexterity, and skill in the use of their weapons; and above all, their few wants, generally ensure them that look of welcome, without which these rovers of the wild will seldom visit a farm or cattle station. Among those, who have become sufficiently acquainted with us, to be sensible of that happy state of security, enjoyed by all men under the protection of our laws, the conduct is strikingly different from that of the natives who remain in a savage state. The latter are named ' myalls,' by their half civilized brethren - who, indeed, hold them so much in dread, that it is seldom possible to prevail on any one to accompany a traveller far into the unexplored parts of the country. At Segenhoe, on a former occasion, I met with a native but recently arrived from the wilds. His terror and suspicion, when required to stand steadily before me, while 1 drew his portrait, were such, that, notwithstanding the power of disguising fear, so remarkable in the savage race, the stout heart of Cambo was overcome, and beat visibly; - the perspiration streamed from his breast, and he was about to sink to the ground, when he at length suddenly darted from my presence; but he speedily returned, bearing in one hard. his club, and in the other his bommereng, with which he seemed to acquire just fortitude enough, to be able to stand on his legs, until I finished the sketch. They understand our looks better than our speech.

December 2nd

- They departed again at 7am and soon came to the farm of Scotsman Hugh Cameron who was known to Mitchell. They stayed a short while and were persuaded by Cameron to drink a ' stirrup-cup' at the door. Meanwhile the rest of the expedition had continued on....We soon overtook the party - and had proceeded with it, some distance, when a soldier of the mounted police came up, and delivered to me a letter, from the military secretary at Sydney, informing me by command of the Acting Governor, that George Clarke - alias ' the Barber,' - (the bushranger,) had sawed off his irons, and escaped from the prison at Bathurst. This intelligence was meant to put me on my guard respecting the natives, for from the well known character of the man, it was supposed, that he would assemble them beyond the settled districts, with a view to drive off the cattle of the colonists - and especial caution would be necessary to prevent a surprise from natives so directed, if, as most people supposed, his story of 'the great river,' had only been an invention of his own, by which he had hoped to improve his chance of escape.

At three P. M., we reached a spot favourable for encamping, the Kingdon brook forming a broad pool, deep enough to bathe in, and the grass in the neighbourhood being very good. The 'burning hill' of ' Wingen' was distant about four miles.

December 3rd

- The party in proceeding, crossed several deep gullies in the neighbourhood of the burning hill; and the road continued to be well marked. At length we began to ascend the chain of hills, which connects Wingen with Mount Murulla and the Liverpool range. On gaining the summit of this range, we overlooked Wingen, whose situation was faintly discernible by the light blue smoke. Three years had elapsed, since my first visit to these slumbering fires. The ridge we were crossing was strewed with fallen trees; and broken branches with the leaves still upon them, marked the effects of some violent and recent storm. We descended to a beautiful valley of considerable extent, watered by Page's river, which rises in the main range. We reached the banks of this stream at four p. M., and encamped on a fine flat. The extremities from the mountains on the north, descend in long and gradual slopes, and are well covered with grass. This was already eaten short by sheep. Two babbling brooks water the flat, at the part where we pitched our tents, and which is opposite to Whalan's station; one of these being the river Page, or 'Macqueen's River;' the other known only as ' the creek.' The space between them is flat, and apparently consists of a soil of excellent quality. The heat of the day was excessive, the thermometer 80 degrees at sunset.December 4

- Mount Murulla is a remarkable cone of the Liverpool range, and being visible from Warrawolong, is consequently an important point in the general survey of the colony. Our way now lay westward, towards the head of this valley, in order to cross by the usual route, the higher and principal range, which still lay to the north. We traversed, this day, six miles of the valley, and encamped beside a remarkable rock, near to which the track turned northward. I rode a little beyond our bivouac, and chanced to fall in with a tribe of natives from Pewen Bewen on Dart Brook, one of whom afterwards visited our camp, but he could tell us little about the interior country. The whole of the valley appears to consist of good land, and the adjacent mountains afford excellent sheep pasture. In the evening, a native of Liverpool plains came to our tents; I gave him a tobacco-pipe, and he promised to shew me the best road across them. Thermometer at sunset 84 degrees.December 5

. - This morning we ascended Liverpool range, which divides the colony from the unexplored country. Having heard much of this difficult pass, we proceeded cautiously, by attaching thirteen bullocks to each cart, and ascending with one at a time. The pass is a low neck, named by the natives Hecknadiiey, but we left the beaten track (which was so very steep that it was usual to unload carts in order to pass) and took a new route, which afforded an easier ascent. All had got up safely, and were proceeding along a level portion, on the opposite side of the range, when the axle of one of the carts broke, and it became necessary to leave it, and place the load on the spare pack-horses, and such of the bullocks, taken out of the shafts, as had been broken in to carry pack-saddles. We reached at length, a water-course called Currungai, and encamped upon its bank, beside the natives from Dart Brook, who had crossed the range before us, apparently to join some of their tribe, who lay at this place extremely ill, being affected with a virulent kind of small-pox. We found the helpless creatures, stretched on their backs, beside the water, under the shade of the wattle or mimosa trees, to avoid the intense heat of the sun. We gave them from our stock some medicine; and the wretched sufferers seemed to place the utmost confidence in its efficacy. I had often indeed occasion to observe, that however obtuse in some things, the aborigines seemed to entertain a sort of superstitious belief, in the virtues of all kinds of physic. I found that this distressed tribe were also strangers in the land, to which they had resorted. Their meekness, as aliens, and their utter ignorance of the country they were in, were very unusual in natives, and excited our sympathy, especially when their demeanour was contrasted with the prouder bearing and intelligence of the native of the plains, who had undertaken to be my guide. Here I at length drank the water of a stream, which flowed into the unexplored interior; and from a hill near our route I beheld, this day, for the first time, a distant blue horizon, exactly resembling that of the ocean.The expedition then proceeded in the direction of the Peel River and afterwards explored to the Namoi and followed it down as far as Narrabri. They then cut across the plains to the Gwydir near Moree.

Several weeks were spent charting the tributaries between the Gwydir and the Barwon and in the process the exaggerated tales related by George Clarke of a vast inland sea were dispelled.[1] Later when he returned from the expedition Mitchell examined George Clarke where he was incarcerated in the hulk, and was satisfied that Clarke had never been beyond the 'Nundawar' Range. [2]

Notes and Links

1). In 1860 Richard Lewis Jenkins purchased Park Hall at Douglas Park, a property owned for many years by Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell. On it stood a magnificent stone mansion the foundation stone of which was laid by Mitchell and Sir Charles Nicholson. The stone had on a long inscription in Latin which translates as follows: Thomas Livingstone Mitchell, Knight Honored Doctor of Civil Laws in the University of Oxford accompanied by Sir Charles Nicholson, Doctor of Medicine in the year of grace 1842 and in the reign of Queen Victoria laid the foundation stone of this house in a land now almost divided from the world, but which it is hoped may one day equal in all the arts of civilisation the illustrious regions of his native country. The house was modelled and named after Park Hall in Stirling Scotland. Richard Jenkins named it Nepean Towers. .....The Farmer and the Settler 18 March 19552). Three Expeditions Into the Interior of Eastern Australia: With Descriptions.. By Thomas Livingstone Mitchell.........Project Gutenberg

3). Diary of Mitchell's youngest daughter Blanche at the State Library of New South Wales

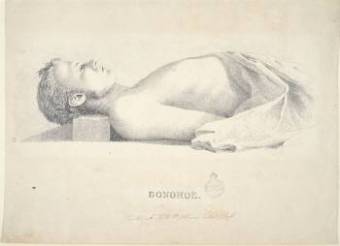

4). Pencil drawing of bushranger Jack Donohoe attributed to Sir Thomas Mitchell who is said to have made it while the body of Donohoe lay in the morgue.

5). In 1834 Mitchell published his famous Map of the Nineteen Counties. The Nineteen Counties were the limits of location in the colony of New South Wales defined by Governor Sir Ralph Darling in 1826. Lieut-Colonel Henry Dumaresq had copies available for purchase at Port Stephens in 1835.

6). Surveying instruments used by Sir Thomas Mitchell during his three expeditions 1831-1846 - National Library of Australia

7). A Tale of Two Maps - NSW in the 1830's by Mitchell and Dixon: Perfection, Probilty and Piracy!. - John F. Brock

8) Thomas Livingstone Mitchell was appointed Captain in the 54th Regiment, West Norfolk Regt. 3 October 1822. A List of the Officers of the Army and of the Corps of Royal Marines By Great Britain. War Office

References

[1] D. W. A. Baker, 'Mitchell, Sir Thomas Livingstone (1792 - 1855)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, published first in hardcopy 1967[2] Three expeditions into the interior of Eastern Australia, with descriptions of the recently explored region of Australia Felix - Sir Thomas Livingstone Mitchell, p. 139

↑