Lime Burning Camp

Fullerton Cove

Governor Macquarie's Building Program

When Governor Macquarie arrived in 1810 he found many public buildings were dilapidated and in need of replacement and he immediately began an extensive program of public works.During his twelve years as Governor, Macquarie oversaw the building of government infrastructure such as the Hyde Park Barracks, Sydney Hospital (now Sydney Mint and NSW Parliament House), St James Church and the Macquarie Lighthouse at the entrance of Sydney Harbour as well as many other projects.

Lime Burning at Newcastle

Lime burning had commenced as early as 1808 at Limburner's Bay at Fullerton Cove on the inner side of the Stockton Peninsula where there was an immense deposit of oyster shells which made good lime.In 1810 pressure from head quarters to provide lime and cedar to support building projects in Sydney became relentless and by August 1810 building had come almost to a standstill for want of lime. Plans were devised for improving productivity at Newcastle. Twenty thousand bricks were requested by the Commandant John Purcell to construct a new lime kiln. . Edward Young arrived on the Admiral Gambier in 1808. A bricklayer by trade, he was sent to build the lime kilns however he was a troublesome man and in December 1810 was punished with 60 lashes for refusing to do public labour and in a most mutinous manner threatening the Commandant. He returned to Sydney early in 1811.

In August 1810 the Lady Nelson was dispatched to the settlement with another limeburner - Flaherty - on board with the hope that productivity would be increased. Lieutenant Purcell received instructions that the Lady Nelson was to return to headquarters with as much lime as could be procured. With the new lime kilns constructed production of lime could be increased and limeburner Anthony Dwyer (Atlas 1802) arrived at Coal River on the Lady Nelson. He was employed as overseer at the Lime burners camp and remained in Newcastle for many years. Two more lime burners were promised and by the end of August limeburner John Anson was sent from head quarters in the hope a full cargo of lime would be ready at all times

See Newcastle in 1810 to find out the progress of building the lime kilns in that year and some of the convicts and overseers who worked at the lime burners camp.

Governor Macquarie inspected the lime kilns in the vicinity of Newcastle when he Toured the Settlement in January 1812[3]

Usually the most desperate convicts were sent to work at the lime kilns and it became a dreaded punishment. The convicts were compelled by threat of the lash to work long hours digging out the shells which were burnt in the kilns. The awaiting ships could not get close to the shore because of shallow water and so convicts carried the lime in sacks out the vessels.

Resources Dwindling 1815

In 1815 the shells and timber needed for producing the lime were running out.An exasperated Commandant Thomas Thompson informed Headquarters of the difficulties he was experiencing:

Sir,

By the arrival of the Lady Nelson on the 10th, I have the Honor to receive your letter of the 8th. In reply to which I beg leave to state, with respect to the lime that from the scarcity of shells and the difficulty of procuring wood, it is totally impossible for me to procure more than three hundred bushels per week during fine weather.

His Excellency the governor cannot be aware of the difficulty in procuring this article arising from the impossibility of my employing the lime burners except on the Islands or northern shore, the shells on which are now nearly consumed, and this only for a few hours at high water, as no boat can approach them at any other times and from its being often the case that shells may be procured where the sea or swamp oak cannot be obtained which prevents their being burned.

My overseer Anthony Dwire (Dwyer) to whom His Excellency has promised a conditional pardon and who of course exerts himself to the utmost of his power informs me that he cannot employ a gang of more than 30 men and I am aware from the opportunities I have had of seeing them at work that a greater number would be useless. I shall however do everything in my power to comply with the demands made on me, but in justice to myself, I cannot help stating the difficulties under which I labour; I am sorry that the cedar sent by the Nelson did not meet His Excellency's approbation. I can only state that I have at present nearly 400 logs of the same dimensions lying on the beach, from the great demands that have been made for cedar on this settlement it is impossible to get logs that will square, except occasionally more than 30 inches

I have sent up a cedar gang yesterday which it is my intention to visit in the course of the week

I shall then be able to give you more information on the subject. I trust and hope His Excellency will give me credit for the exertions I have used since I had the honor of Commanding the station for I can assure you I have done everything my limited means would allow for the good of the service.

I have the honor to be

Your obedient servant

Thomas Thompson, Commandant [2]

Settlers and Convicts

Excerpt from Settlers and Convicts: Or Recollections of Sixteen Years' Labour in the Australian Backwoods. By Alexander Harris. p11 -How long have been here then, Sir?' I inquired.

'Nearly a score years. I have seen a good deal with my own eyes, and that makes me believe other things that I have only been told. And then, again, I have often heard men, after they became free, throw into the teeth of overseers the usage they had received at their hands. I recollect once, in coming over the blue mountains, it set in to rain very hard, and by the time we got to the punt at Richmond the Hawkesbury River was up, and there was no getting over. Nearly a hundred of us were gathered together about the public house at the ferry. And here one of the labouring men recognized an overseer who had been over him at the lime burners' gang at Newcastle. The overseer stoutly contended that he was not the person; but it was of no use. I made sure he'd have got his brains knocked out, and no doubt he would, had not the landlord shut him up in his room"

'What had he done?'

'Oh, nothing more than the other overseers, so far as I heard: but certainly that was enough, when we come to consider; for men are men, and not beasts, let 'em be ever such thieves. From all accounts there were some dark doings at that lime burners' gang. I have heard from twenty sources that Red...., the overseer, was known to have killed a man with a handspike, and was never tried for it. The commandant was as big a brute as he was, and so was not likely to bring him to justice; and the men were all afraid to say anything. It is a well known fact that they used to rouse up the poor half starved skeletons of fellows at midnight to load lime, when the boats happened to come in with a night's tide.

They used to have to carry the baskets of un-slacked lime a great way into the water in loading the boats; by which means many of their backs were raw, and eaten into holes. But that made no difference. The work they must do. The shed they had to sleep in was close by the waterside; and the slabs were so wide apart that you might almost have galloped a horse through. Many of them at one time, had scarcely a rag of clothes; nothing more indeed than some piece of an old red shirt that they tied round their middle, and neither bed nor blanket. A man who worked for me told me that such was his case for a long time; and that for warmth they used to gather sea weed off the beach, and spread it some inches thick on the floor of the hut; and numbers of them would turn in together, covering themselves over with it, and getting warmth from the fermentation of the sea weed; you may say, in short, they buried themselves in a dunghill to keep warm.

Description of the Process in 1819

William C. Wentworth described the process used near Newcastle in 1819..... The lime produced at this settlement is made from oyster shells ... The process of making lime from them is extremely simple and expeditious. They are first dug up and sifted, and then piled over large heaps of dry wood, which are set fire to, and speedily convert the super incumbent mass into excellent lime. When thus made it is shipped for Sydney, and sold at one shilling per bushelJohn Thomas Bigge's Report on the Lime Burners

John Thomas Bigge described the lime burners in his Report of Inquiry in 1822 -The last mode of employment, or rather of punishment, for men who are found to be refractory, or sent with bad characters from the other settlements, ii is that of collecting oyster shells and burning them into lime. The place selected for this operation is a peninsula of low land, that is separated from the settlement of Newcastle by the Hunter's River in front, on the eastern side by the sea, and on the western by the large and spreading inlets of the river. The place of labour is about six miles from Newcastle.

The convicts are lodged in one wooden building, and are guarded by a corporal's guard, and superintended by one overseer, who is a convict. Each convict is tasked to procure a certain quantity of shells, which are found in a loose and rich deposit of sandy loam, that is easily removed. The shells are thrown into heaps, after being disengaged from the loam, and burnt into lime with logs of wood. The loading of the boats with lime is a part of the operation that has been complained of, as on account of the shallowness of the shore the boats are moored at some little distance, and the lime is carried in baskets on the shoulders of the convicts and deposited in the boats. I found that this operation was performed only once a month; but from the spray of the sea mixing with the lime, and the shoulders of the convicts being without protection, it sometimes happens that they are slightly burnt. The eyes of the men also employed in burning lime are affected by the smoke, but not in a greater degree than in England; and I found that they were in the habit of exposing themselves, unnecessarily, to the smoke of the lime kilns, that the state of their eyes might afford a pretext for their removal from the settlement.

Frequent communications take place between the lime-burners station and Newcastle, and the nature of the punishment consists in the removal of the convicts from their associates, and in the difficulty that they find in obtaining an increased quantity of food, or in exchanging their rations for tobacco. [1]

Burning Shells to Make Lime

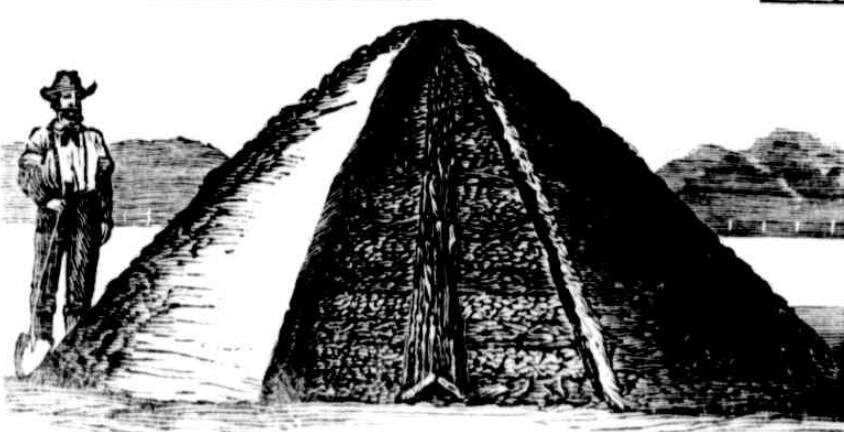

The engraving shows the usual method of burning shells for lime in pits or heaps. To burn the shells a level spot should be made about twelve feet in diameter. A quantity of rough brushwood is then laid down several inches in thickness, leaving four or more open draft ways or flues from the outside to the centre. Fine kindling wood is laid in these draft ways. A flue of sticks, placed upon their ends is also made in the centre of the heap connecting with these draft ways. Upon this lower layer of wood a foot in thickness of shells is placed, then a layer of wood and then one of the shells alternating with shells and wood, and gradually drawing in the heap until a conical pile about eight feet high is made [5]....continue

The engraving shows the usual method of burning shells for lime in pits or heaps. To burn the shells a level spot should be made about twelve feet in diameter. A quantity of rough brushwood is then laid down several inches in thickness, leaving four or more open draft ways or flues from the outside to the centre. Fine kindling wood is laid in these draft ways. A flue of sticks, placed upon their ends is also made in the centre of the heap connecting with these draft ways. Upon this lower layer of wood a foot in thickness of shells is placed, then a layer of wood and then one of the shells alternating with shells and wood, and gradually drawing in the heap until a conical pile about eight feet high is made [5]....continueReferences

[1] House of Lords Sessional Papers[2] Colonial Secretary's Correspondence, Commandant Thomas Thompson to Headquarters 12 September 1815. Reel 6066; 4/1805 p.195

[3] Historical Records NSW, Vol. VII, p. 486

[4] Wentworth, W.C. 1819. Statistical, Historical and Political Description of the Colony of New South Wales. Whittaker, London

[5] Australian Town and Country Journal 13 June 1874

↑